Earth’s atmosphere has long served as a free dump for carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases generated by humans. That is changing as policy-makers embrace economists’ advice that the best way to cut greenhouse gas emissions is to charge an atmospheric disposal fee. As a result, governments are increasingly tacking on a price for carbon when fossil fuels are sold and/or consumed, allowing their economies to internalize some of the social and economic costs associated with burning coal, oil and natural gas.

In theory, billing polluters for every ton of carbon they unleash should drive emissions reductions with great economic efficiency, since each player is free to choose its optimal response to the carbon price. Those who can cut affordably do so. Those who can’t, pay the price.

“Carbon pricing is the most effective policy for reducing emissions,” says Christine Lagarde, managing director of the Washington, D.C.–based International Monetary Fund, which is a global cheerleader for carbon pricing.

Schemes turning theory into practice applied a carbon price to the equivalent of about 7 billion metric tons (7.7 billion tons) of CO2 emissions worldwide last year, according to the World Bank (another carbon pricing booster). That represents about 12 percent of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. And the World Bank and IMF have set a goal to extend carbon pricing’s footprint to 25 percent of global emissions by 2020.

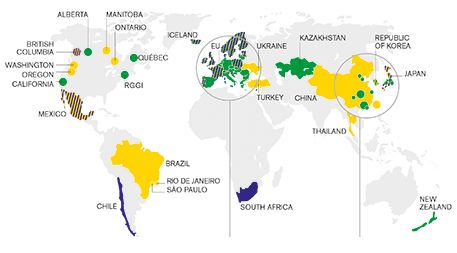

Graphic of global emissions trading systems and carbon taxes adapted from World Bank Group: State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2015. Large circles represent subnational instruments; small circles represent cities. Click for full view.

What carbon pricing pioneers have yet to prove, however, is that it can deliver on its potential. To date most carbon prices remain low — “virtually valueless” is how Bloomberg put it in a recent review of carbon pricing. That has led even some economists to question whether carbon pricing’s theoretical elegance may be outweighed by practical and political hurdles.

Trade vs. Tax

Although there are many variations on the theme, carbon pricing basically takes two forms.

In most cases, carbon prices are set by national, regional or municipal carbon markets. Governments create these markets by putting an upper limit on total annual greenhouse gas emissions for given sectors of their economies, then issuing tradable “allowances” or “credits” for those emissions. More than a dozen carbon markets are now operating, putting a price on 8 percent of global GHG emissions. In the past five years new carbon markets have been launched in California, Quebec, South Korea, and major Chinese industrial centers such as Shanghai, Tianjin and Guangdong.

A simpler option, a carbon tax, currently puts a price on about 4 percent of global GHG emissions. Instead of conjuring up markets to set carbon prices, carbon taxes impose direct levies on industries for every ton of CO2 they release, or on consumers for every ton of CO2 in the fuels they use.

Carbon taxes present a challenge for politicians facing tax-averse publics, but a number of jurisdictions have adopted them, including the U.K., British Columbia and South Africa. Carbon taxes also appear to be gaining some traction in the U.S.: Senator Bernie Sanders made them a central plank in his recent presidential bid, and Washington State voters will get a vote on the first state-level carbon tax ballot initiative in November.

Experts say the two approaches to carbon pricing share more similarities than differences. Unfortunately, their similarities include chronically low prices — prices too low to drive substantial emissions reductions or to inspire low-carbon investments. Most carbon markets and taxes are well below US$15 per metric ton (1.1 ton), whereas members of the International Emissions Trading Association recently estimated that €40 (US$44) per metric ton (1.1 ton) pricing was required to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

The problem, Jaccard says, is that carbon pricing is as politically inexpedient as it is economically efficient.“It is politically difficult to get carbon prices to levels that have an effect,” says Mark Jaccard, an energy economist at British Columbia’s Simon Fraser University. The problem, Jaccard says, is that carbon pricing is as politically inexpedient as it is economically efficient: “While carbon pricing has become a mantra for economists, environmentalists, academics, celebrities, media pundits and even corporate heads, none of these people needs to get reelected,” he notes.

Tough Trading

Carbon markets have been a work in progress ever since the European Union launched the first one in 2005 to comply with the Kyoto Protocol, under which the EU pledged to cut emissions to 8 percent below 1990 levels by 2012. The EU’s Emissions Trading System is vast and complex, covering nearly half of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions, including those from over 11,000 cement plants, power stations, refineries and other polluting installations as well as CO2 from air travel within Europe.

The ETS releases 1.74 percent fewer allowances for industrial emissions every year, so emissions should be 21 percent lower in 2020 than they were in 2005. In practice, emissions are dropping, but not because of the market, which suffers from a chronic glut of allowances.

Dallas Burtraw, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future, a Washington, D.C.–based think tank, says the ETS allowed polluters to make generous use of carbon offsets — allowances generated by emissions reduction projects in developing countries. At the same time, economic recession gripping Europe since 2008 and European regulations promoting renewable energy and efficiency both cut fossil fuel consumption, reducing demand for ETS allowances.

The result is rock-bottom pricing for carbon. In late June 2016, European allowances were trading at €4.50 (US$5.00) per metric ton (1.1 ton), less than one-third their initial price in 2005. “The ETS price is below expectations, and below the level that could spark transformational innovation and investments,” says Burtraw.

Some newer markets have sought to avoid Europe’s troubles, with qualified success. Academic researchers concur. A 2013 research survey by the U.K.-based Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, for example, estimated that the ETS was having a “small but non-trivial impact” on European carbon emissions. It found no evidence that carbon pricing was driving investments in new equipment or innovation needed to meet the EU’s long-term emissions targets.

Some newer markets have sought to avoid Europe’s troubles, with qualified success. One launched in 2012 by California (and pooled with Québec’s carbon market in 2014) fights oversupply by allocating most allowances via auctions with a floor price that rises every year, instead of handing them out for free.

Despite this strategy, the California/Québec carbon price also crashed after a few years. It currently sits near the latest auction floor price of US$12.73 — a price level that puts little downward pressure on emissions. Jaccard argues that policies such as California’s renewable portfolio standard, which has fueled aggressive deployment of utility-scale solar and wind farms, are driving California’s emissions reductions. “The cap is not actually forcing down emissions. Regulations are,” he says.

The market, meanwhile, is proving a wild ride for public finances, despite its floor price. Most allowances did not sell at California’s May 2016 auction, thanks at least in part to a legal challenge by manufacturers that spooked traders’ confidence in the market. The state put 43 million allowances to auction and sold just 785,000, all at the floor price. The results were a rude surprise for state agencies promised auction proceeds to fund climate and energy programs. The agency designing a high-speed rail network for California, for example, expected at least a US$150 million infusion from last month’s quarterly auction and instead netted just US$2.5 million.

The world’s leading greenhouse-gas emitting nation, China is planning to institute a carbon market in 2017. Photo © iStockphoto.com/powerofforever

China is preparing to start a national carbon market next year that will eclipse the EU’s as the world’s largest, covering roughly 4 billion metric tons (4.4 billion tons) of CO2. Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the 2017 carbon market launch last fall to reinforce the country’s promise under the Paris Agreement for its CO2 emissions to peak by 2030.

There is no evidence yet that China’s market will produce stronger carbon prices than its predecessors. While the rules are still being decided, experts expect that it will launch with free distribution of allowances. “There will be mostly free allocation, but auctioning — presumably with a reserve price — will play an increasingly important role over time,” predicts Clayton Munnings, a colleague of Burtraw’s and a China expert at Resources for the Future.

Munnings led a study of China’s regional pilot carbon markets (to be published soon in Energy Policy) that identified enforcement and transparency concerns that could also undermine the national market.

“Credibility is important to cap-and-trade markets,” he says. “Firms must believe that allowances are scarce if they are to fully participate in trading.”

Taxing Strategy

Carbon tax advocates favor forgoing the vagaries of carbon markets altogether. Rather, they recommend governments tax greenhouse gas production at a rate that will create sufficient incentive to significantly reduce emissions while generating steady revenues that can be put to good use.

The quintessential example is British Columbia’s carbon tax, which adds C$30 (US$23) per metric ton to fossil fuels sold and combusted in the province (which account for over 70 percent of its total greenhouse gas emissions). It is generally accepted that the tax is reducing emissions in British Columbia without harming the provincial economy.

Supporters rally in favor of Washington State’s Initiative 732, which would tax carbon emissions and distribute revenues in the form of tax cuts. Photo courtesy of Carbon Washington

Yoram Bauman, the Seattle-based economist behind Washington State’s ballot Initiative 732, says he modeled the carbon tax ballot measure after British Columbia’s. Bauman says he fell in love with the “simplicity” of environmental taxation as an undergraduate at Reed College in Portland, and found the province’s carbon tax elegant enough to capture in haiku:

Fossil CO2 / 30 dollars for each ton / Revenue neutral

British Columbia’s policy returns revenues from the carbon tax to taxpayers in the form of cuts to existing taxes — and that’s the plan for Initiative 732 as well. Both also offer tax benefits for low-income families, who are disproportionately hurt by rising energy costs.

In British Columbia, this revenue neutral formula drove a rapid reduction in CO2 emissions at little cost to the economy during its first four years, with per capita use of fossil fuel dropping up to 19 percent. Several studies suggest that British Columbia’s economy may have actually accelerated as a result thanks to the stimulative effect of cutting income and business taxes. A 2015 working paper from the University of Calgary, for example, estimates that employment in the province grew 2 percent between 2007 and 2013 due to the carbon tax.

That double dividend is attracting politically diverse interest in the U.S. Former Cato Institute official Jerry Taylor, who now runs the libertarian Niskanen Center, issued a report last year titled The Conservative Case for a Carbon Tax. More recently, Sen. Bernie Sanders has been trying to convince the Democratic Party to endorse carbon taxes.

Republican leaders in Congress who oppose climate action passed a nonbinding resolution in June stating that carbon taxes “would be detrimental to American families and businesses.” But Aparna Mathur, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, bemoaned the Republican’s resolution this month, telling Politico that “instead of relying on dozens of federal and state regulations that themselves are costly, a carbon tax would be transparent and cost-effective.”

Yet the political hurdles facing carbon taxes cannot be overstated. Representatives of U.S. presidential candidate Hillary Clinton opposed including Sanders’ carbon tax plank in the Democratic Party’s official 2016 platform. And even supporters of Initiative 732 say it faces an uphill battle.

“We have a very tax-sensitive electorate in Washington,” acknowledges Joe Fitzgibbon, chair of the Washington State legislature’s environment committee. Others have expressed concerns that the initiative could leave the state with less revenue. And environmental groups are rallying instead behind cap and trade, with revenues to be redirected to environmental programs (including ones protecting the state’s forestry jobs) rather than tax cuts.

Even British Columbia’s much-lauded carbon tax is unpopular at home and losing ground. Annual increases in the tax were frozen in 2012, when Premier Gordon Campbell, who launched the tax, left office. And the province’s greenhouse gas emissions are on the rise again. Seven members of current Premier Christy Clark’s Climate Leadership Team recently urged her in an open letter and op-ed to strengthen the tax. The advisors have recommended C$10 (US$23) per metric ton (1.1 ton) annual increases from 2018 to provide “enough incentive to reduce carbon pollution.”

The Regulation Option

Jaccard, who advised Campbell on the original tax plan, claims to have lost faith in the political viability of carbon pricing. He is providing advice to Canada’s federal government, and suggesting Prime Minister Justin Trudeau focus on regulations that have direct and proven impact.

Modeling by Jaccard’s research group suggests that Canada would need carbon prices rising to C$160 (US$124) per metric ton (1.1 tons) in 2030 to meet its pledges under the Paris agreement. Instead of risking political careers with such a proposal, he advises politicians to strengthen carbon-cutting regulations. For example, he suggests mandating a phase-out of coal-fired power plants and requiring automakers to sell mostly electric vehicles by 2030.

“Difficult as this might be, it would be far less difficult than defending a rapidly rising carbon tax that attracts hostile media attention with each increase,” Jaccard wrote recently in the Canadian online magazine Policy Options.

[R]esearch indicates that carbon pricing policy is consistently undermined by lobbying from commercial interests. Steffen Böhm, an expert in carbon markets at the University of Exeter Business School in the U.K., has come to the same conclusion. He says that his research indicates that carbon pricing policy is consistently undermined by lobbying from commercial interests.

“What we need is policy-makers taking responsibility to put legislation in place to phase out fossil fuels,” says Böhm.

Others expect carbon markets to deliver in the end, with prices rising as lower-cost emissions reductions are exploited and declining carbon caps force increasingly tougher action.

Burtraw at Resources for the Future offers an alternate and rather unorthodox possibility: Low carbon prices may reflect factors like innovation that are impossible to fully anticipate. He notes the plummeting prices for solar and wind power and energy efficiency measures. Whereas the fossil fuels that have dominated economies for centuries tend to rise in cost as they are depleted, renewables are dropping fast and they could keep on dropping. As a result, climate mitigation could turn out to be less expensive than economists have assumed.

“My view is that a carbon price is imperative,” says Burtraw, “but in the end it will not have to be high.”

The post If carbon pricing is so great, why isn’t it working? appeared first on Ensia.